🇯🇵 Japan – the end

67 days and 6,839km (Total: 225 days and 38,983km)

After riding for six months, through twenty five countries, and covering thirty two thousand kilometers, we rode K off the Eastern Dream ferry and into the port of Sakaiminato, serendipitously back on the left hand side of the road for the first time since Jersey. We had reached Japan.

Our original plan was to ride straight to Tokyo and put K on a ferry back to Jersey. But the sun was still warm, the trees were turning autumnal red, and we had no jobs or responsibilities to return to. We were on a Japanese motorcycle in a country obsessed with motorcycle travel. So we changed our plan: let’s ride around Japan.

That's what we've been doing for the last two months. Riding the back roads of Japan, staying in a new town almost every night, and experiencing more of this deeply fascinating country that we fell in love with when we first visited a decade ago.

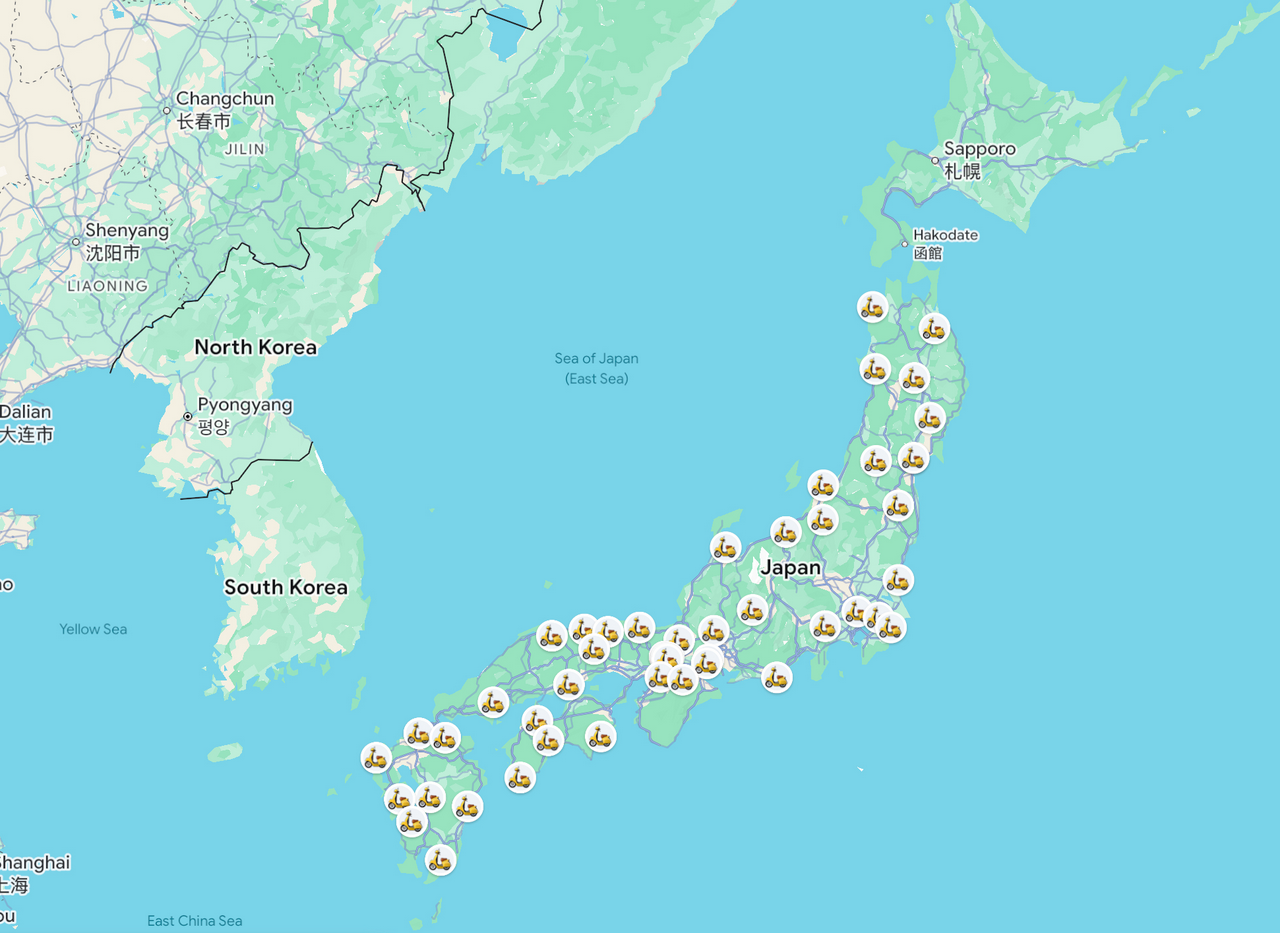

My Google maps pins are now yellow scooters instead of red racing bikes because the riding itself has been less adventurous. Slower, shorter, safer. Pristine roads and no crazy drivers. It took at least a few weeks before we heard anyone beep their horn. And about the same time for us to learn that skipping traffic is a total no-go. Putting on our boots each morning used to feel like we were preparing for an intense bootcamp, now it feels like we‘re getting ready for a jolly day out.

Japan has been amazing to experience, but impossible to fully understand. Everything runs on this fine line between ultra-sophistication and pure simplicity. Traffic lights feel telepathic, knowing exactly who to release and when. Convenience stores stock whatever you might need — new socks, chilli oil, a printer, even a porn magazine. After a month in Mongolia and Siberia, the cleanliness was a shock (in a good way). Public toilets are as spotless as those in five-star hotels, petrol pumps shinier than my cutlery at home, and onsens where everyone scrubs themselves half a kilo lighter before getting into the bath. My continued wonder is how the streets stay so immaculate in a country with no public bins.

There seems to be this grounding of trust, unity, and peace that sits quietly beneath everything. But it’s not the feeling of oppression. In most places where things “work,” you can sense the machinery behind it — rules, cameras, police, consequences. Japan feels different. There’s no heaviness from above, just a kind of responsibility from the side. Everyone queues without being asked, returns the umbrellas they borrowed, leaves bikes unlocked, and respects each other’s space. It seems like something fragile and easy to break… but it doesn’t. It just flows, in a collective harmony.

The other thing we noticed was how big camping culture is here. But our tent hasn’t left the pannier since we arrived. Partly because it’s dark and cold by 5pm, but mostly because we’ve loved staying in local inns. We could usually find a ryokan for €40–50 a night. Adding meals almost doubled the price, but the food was worth it: of portion of meat, an array of fish, fresh vegetables, miso soup, unlimited rice, and occasionally a cow tongue. There was often a large shared bath — sometimes pre-filled and kept warm — and, if we were lucky, yukatas to wander around in. Most of our hosts spoke zero English, but they always had endless patience with our Google Translate attempts before showing us around their home, each one unique in some special way.

Our eight-month adventure ended on the Japanese island of Kyushu. We were the furthest we’d ever been from where we’d started, yet K was back at the factory where it was built, after we’d been personally invited to the Honda Motorcycle HQ in Kumamoto. The instructions were very Japanese: “Arrive at 14:30 for a meeting that will start at 14.40 and finish at 16:30.” By this point we knew those timings wouldn’t be a second off, so we showed up ten minutes early with absolutely no idea what we were walking into.

At precisely 14:30, a group of ten Honda employees in white lab coats and Honda caps walked out to meet us. They introduced themselves: the three-person Africa Twin research and development team, two Africa Twin engineers, a four-person marketing team, and Remi, who was running the whole visit.

They took us on a tour of the factory (no photos allowed) where we watched each stage of the Africa Twin production line. A conveyor belt, a station every five metres, and a Japanese engineer solely focused on one specific task. Machines or computers weren’t building the bike, they were double-checking the humans had done it perfectly. At the end of the line the finished bikes were tested; anything that didn’t pass went left, anything that did went right and straight into a lorry to be shipped and sold somewhere in the world — hopefully to become vehicles for journeys of a lifetime, like ours.

We have now left Japan for South Korea, which we’ll explore in the cold before K is put in a crate and shipped back to Europe, and we figure out what adventure comes next.

Our Road to Tokyo ends here. Thanks for reading.